Coffee Certification Challenges

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

But when we look closely at the climate impact on coffee, the consequences are far from trivial. Coffee is an important indicator of global climate instability — and it’s already being reshaped by shifting temperatures and growing conditions, through land conversions, deforestation, or the outright loss of environmental conditions suitable for the coffee tree.

This volatility is exacerbated by the delicate nature of coffee cultivation – particularly Arabica coffee. Coffee requires a rather specific balance of altitude, soil conditions, wet/dry seasons, and temperature to thrive. Small changes to these components lead to terroir-based flavor profiles in coffee, which, like wine, are considered desirable. But when one or more variable in this equation changes too much, the system falls out of alignment and coffee cultivation is no longer sustainable.

In certain cases, one of these variables can compensate for changes to another variable. As an example, if temperatures are expected to rise above the desired threshold for coffee cultivation, it’s possible to push cultivation areas to higher elevations with cooler temperatures. But then, those higher-altitude lands must exist, they must be available, they must be able to be repurposed, and so forth. Offsetting such land losses with gains elsewhere won’t be easy, or quick.

And other variables may still push this equilibrium out of alignment. Fungus and pests can emerge at higher temperatures, complicating any expensive mitigation strategy.

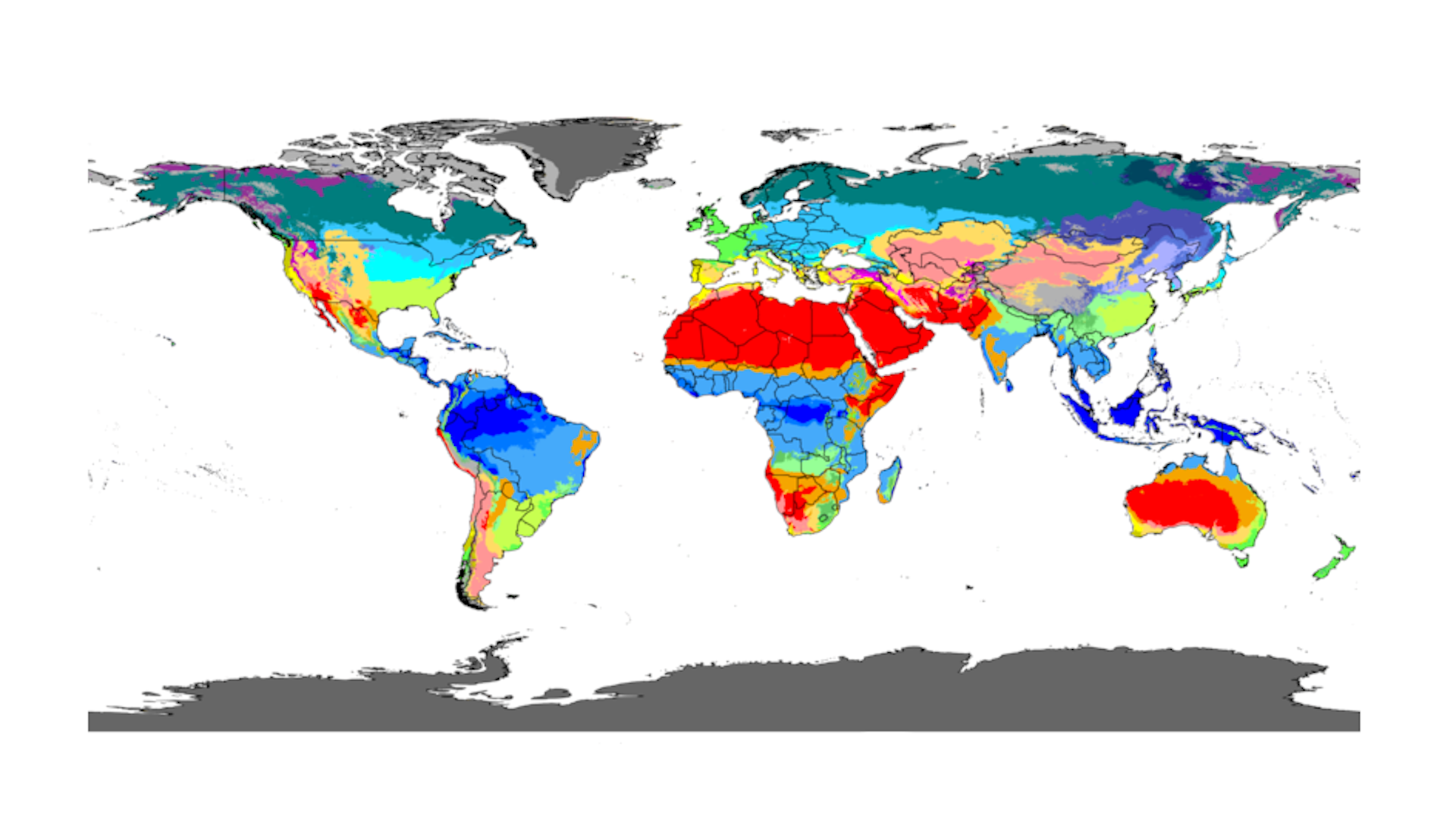

A climate-based map is a good way to illustrate how susceptible coffee is to climate change. The Koppen climate classification system defines climate areas by precipitation and temperature and classifies 30 different categories of climate across the globe.

You can see in the image at the top of page that there are mainly shades of blue around the equator, which is the center point of the “coffee belt”, where most of the world’s coffee is grown.

The lighter blue classification, across large areas of Brazil and central Africa, is a tropical wet/dry & savanna climate. These climates possess the criteria conducive to growing and harvesting coffee: distinct wet and dry seasons, and ideal range-bound temperatures. Plus, they have a range of altitudes and nutrient-rich soils.

It takes just a casual review of the global Koppen map to see how delicate the whole system is.

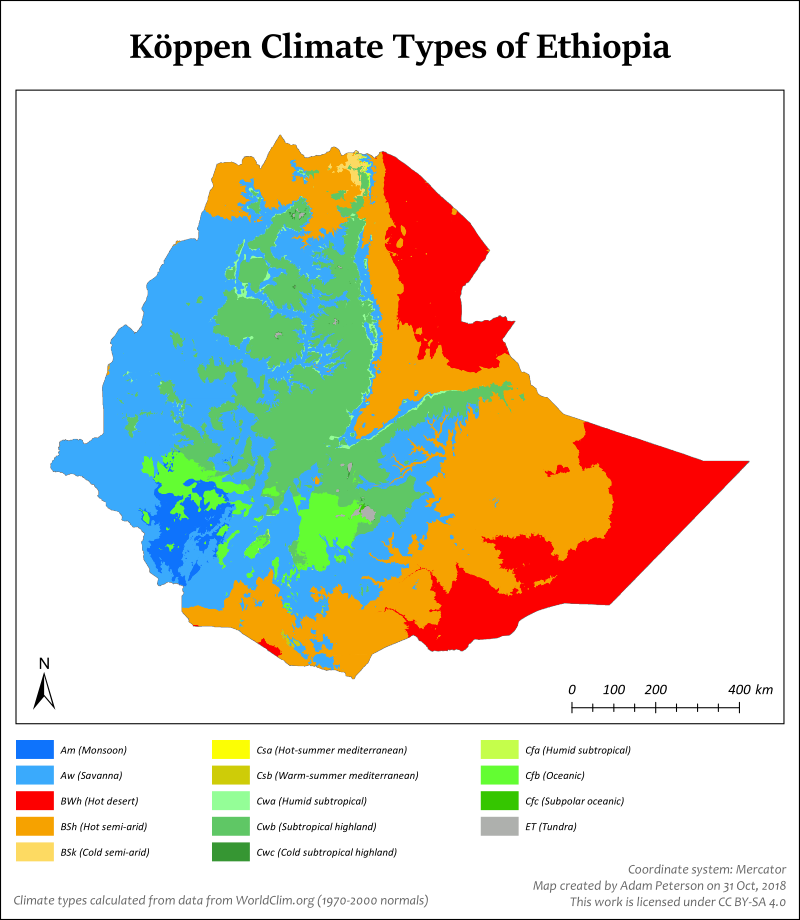

Below is a close-up Koppen map of Ethiopia – a great example of the various microclimates and patterns.

Even small changes to temperature and precipitation levels can alter the map.

And, as we see in many places already, climate change is about extremes. It’s about pushing historically range-bound precipitation and temperatures out of those ranges, often via catastrophic events. That is precisely the type of volatility that is bad for coffee cultivation.

Traceability is an important concept here. The more visibility end consumers can get into the supply chain, the more influence they can exert on rewarding roasters, and in turn farmers, who are using sustainable methods. Coffee growers won’t save the planet by themselves, but it is something that the coffee market can offer and push for.

As a coffee drinker, it’s always good to remember that brewing coffee is just the final step of a very long coffee supply chain, and that, while it may seem distant, the interplay between coffee and climate change is strong and something worth paying attention to.

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

Each quarter in our benchmarking report, we analyze a broad sample of single origin coffees from hundreds of small roasters …

You read tasting notes because they promise an experience. Yet the language on coffee bags often feels repetitive …