Coffee Certification Challenges

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

When it comes to climate change, coffee is both a problem and a solution. Every step of the coffee supply chain potentially contributes to a warming planet:

But all of these areas of concern also present discrete areas for improvement. That is what we want to highlight on this site.

Specific projections differ, but there is general consensus that the land currently suitable and available for growing Arabica coffee around the world will be reduced by as much as 50% by 2050, due to the effects of climate change.

Some local adjustments are feasible, such as attempting to move crops to higher altitudes to combat warmer land surface temperatures. Efforts are also underway to better understand Arabica coffee’s resilience to changing environmental factors, but that research could take years to finalize.

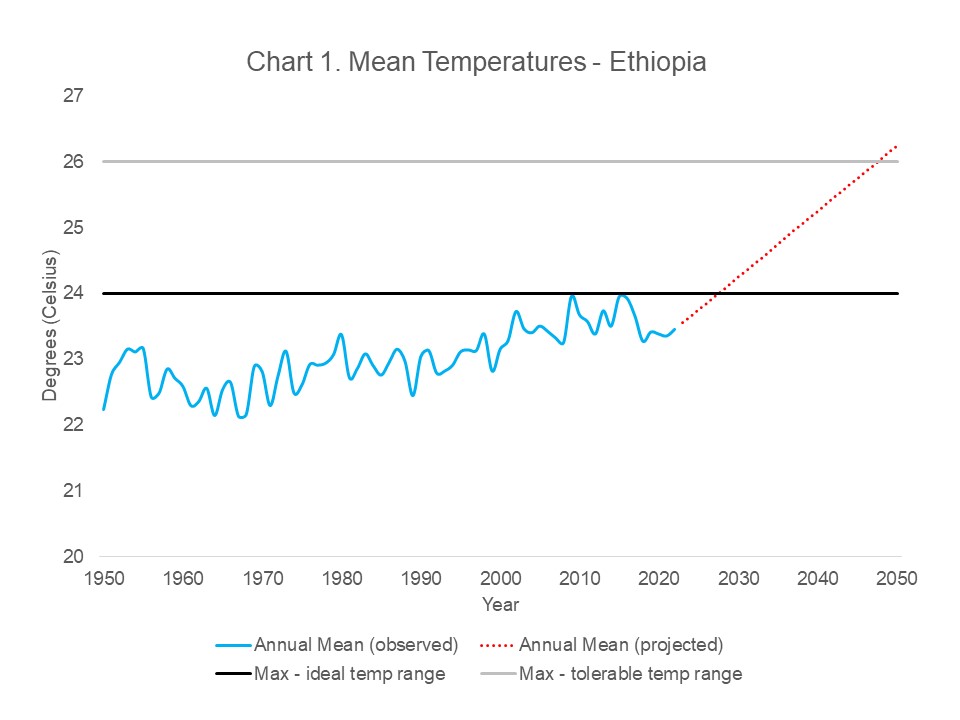

Chart 1 below shows the increase in mean surface temperatures in Ethiopia (one of the largest global exporters of coffee – 220,000 60-kilo bags in January 2022 alone) since 1950. The top of the ideal temperature range for growing Arabica coffee is about 24 degrees Celsius, and observed mean temperatures are already there. Going forward, mean temperatures are projected to far surpass the top of the ideal range, and, in the not too distant future, exceed the maximum temperature that Arabica can even tolerate. At that temperature, most Arabica crops will already be failing.

Arabica is not the only coffee species, and in fact other species are known to be more hearty and resilient when it comes to cultivation. However, these other species (i.e. Robusta or Liberica) have not been successfully integrated into the specialty coffee market in any meaningful way. And for good reason: they just don’t taste the same. If you are a casual buyer of high quality roasted coffee, you probably have only ever bought Arabica. Still, a few roasters are starting to experiment with these alternative offerings.

Often unseen by US coffee drinkers is that tens of millions of people around the globe depend on coffee for their livelihoods. Most of all, farmers, who in many cases already live in regions with severe socioeconomic and climate challenges. Layer in the disappearance of their major source of income, and it is easy to see what is at stake here.

Specific projections also differ on this, though the conclusion is clear: even as land suitable for growing coffee is under threat, global demand for specialty coffee is expanding.

With estimates of up to $120B in global spending by 2030 on specialty coffee, a lot of money is going to change hands.

$120B, or anything in that ballpark, is a massive collective investment. Whatever your portion of that figure might be, think of it like the global community of coffee drinkers is writing a huge check to coffee producers. We can either write that check in a way that rewards outdated practices harmful to the environment and the future of coffee, or we can make that check out to roasters who, from the top-down, are improving the livelihoods of the farmers they work with, are encouraging experimentation with new coffee species, and are champions of sustainability.

An unfortunate hallmark of the coffee market is that reward is not proportional to risk. Farmers take on a lot of the risk and cost of cultivating coffee, yet the largest markups are only applied near the end of the value chain. Even most roasters would probably agree that these dynamics are skewed.

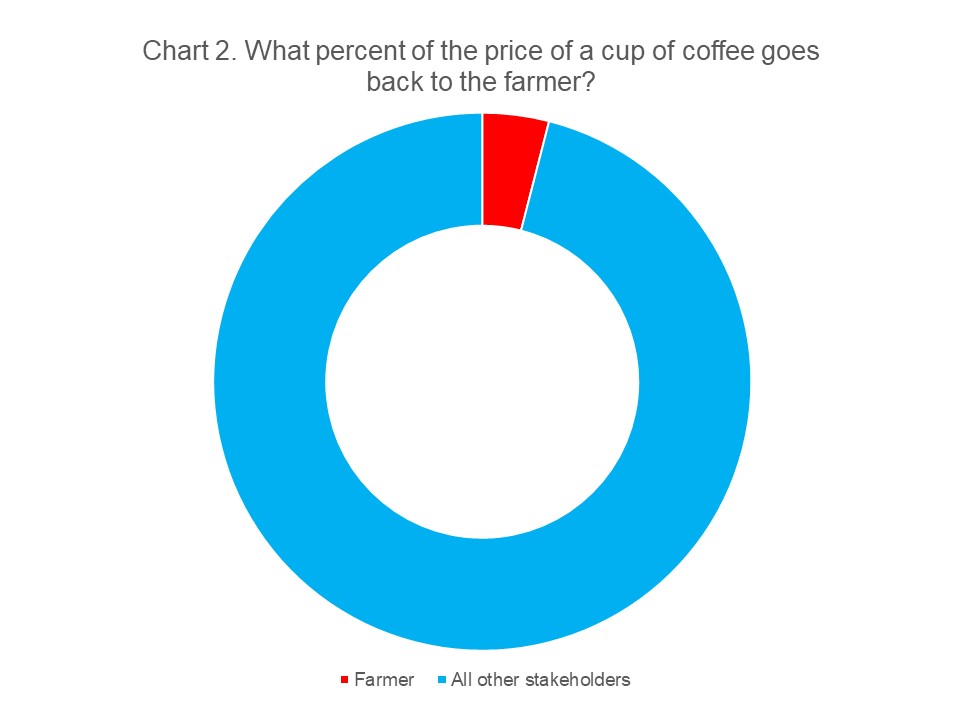

Chart 2 below shows the essence of the economic problem. Visibility into these dynamics is not perfect, so sources differ on how much coffee revenue actually trickles down to the farmers. Yet, even without numbers in this chart you can see the tiny red slice that, according to most sources, is about what the farmers get.

A buyer-driven market can be seen as exploitative, in that the farmers do not possess the same market information as buyers do about demand and willingness to pay. Buyers can also decide what crop lots to purchase or pass on, which is a normal market dynamic but is amplified in coffee since the sellers may not have an alternative buyer lined up.

Information asymmetries are not sustainable especially when farmers are barely making subsistence level income as it is. The solution here is creating purchasing arrangements that spread the value more evenly and in a regenerative way. Only then can a livelihood based on growing coffee become sustainable long-term.

That might mean more of the net income from a retail bag of coffee goes to the farmer instead of the roaster. Or, maybe that means end retail prices will increase. Roasters carry their own substantial costs and risks, so it is not quite a zero-sum game of risk and reward.

Still, roasters are the tip of the spear in seeing that these adjustments are made downstream. The irony here is that roasters who play the short game and do not focus on sustainable livelihoods for farmers are ensuring that those same farmers will move to other crops and income sources and further reduce coffee yields globally.

Roasting specialty coffee is also becoming a more fragmented business, as new roasting technologies are enabling stakeholders that were once net buyers of roasted coffee (i.e. cafes, farm-to-table restaurants) to now roast their own coffee.

This shift in the market will allow for more creativity as smaller roasters take new approaches to roasting and experiment with new origins. It also means that achieving a cohesive industry standard on sustainable roasting practices will become more difficult.

Lack of overall coordination and leadership is already a challenge in global sustainability management, and on a smaller scale, further decentralization of the roasting market will make it more challenging to unite local roasters around a large-scale strategy.

A core part of Lightyear’s mission is predicated on correct measurement of what’s happening in the specialty coffee market.

We have researched over 500 roasters across the US along with thousands of their coffees to learn what innovation really looks like in specialty coffee – what origins are becoming more or less prominent? How are new processing methods changing traditional taste profiles? Beyond the menus you see in roasteries or cafes or in their marketing or branding, what does an innovative roaster look like? Check out our data visualizations to learn more.

More broadly, successful sustainability initiatives globally need to be measured properly, since only then can they be managed effectively. We fully support this data-driven approach so that the correct indicators and metrics are being measured from the start.

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

Each quarter in our benchmarking report, we analyze a broad sample of single origin coffees from hundreds of small roasters …

You read tasting notes because they promise an experience. Yet the language on coffee bags often feels repetitive …

© 2026 Lightyear Coffee LLC

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use