Coffee Certification Challenges

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

How coffee is valued and paid for goes to the heart of the sustainability question. A significant part of what will make coffee “sustainable” in the future is equal value distribution to coffee farmers. This would provide sustainable wages commensurate with the value they create, and would further economically incentivize farmers to keep producing coffee, as opposed to other crops.

Part of what defines a commodity is that it is an unspecialized product that can be treated as interchangeable from one producer/source to the next. Corn from one farm is undifferentiated from corn at another farm. Oil from different regions can be used for the same exact purpose. That all certainly fits with grain, cocoa, cotton and other goods. Does coffee fit this definition?

Coffee is a crop, traded and exchanged consistent with other commodities. If we assume uniform quality across coffee produced in different origins, then absolutely coffee would fit the basic definition of a commodity. But what about coffee at the highest end of the quality spectrum, what is called “specialty coffee”?

Specialty coffee has traditionally been defined as having little to no defects and scoring above an 80 on a 100-point assessment by a certified grader (see the Specialty Coffee Association value assessment here). And to define “specialty” even more precisely, the industry is moving toward including sensory attributes as core parts of how relative value and quality are determined. Coffees meeting these criteria are very much differentiated, which is inconsistent with the definition of a commodity.

Arabica coffee is traded in a commodity market that establishes a base market clearing price (the “C-price”). Various subsequent adjustments can be made to this price however, to account for quality factors that add more value to the coffee than the C-price alone can capture.

Coffee can be bought and sold via different trading models like fair trade or direct trade, at whatever price is agreed upon by buyer and seller.

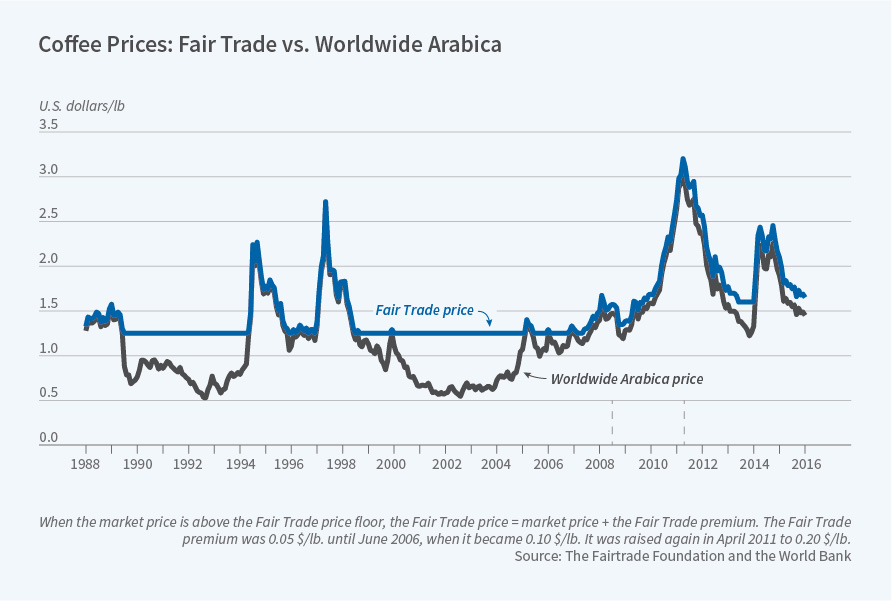

Fair trade programs pay farmers a guaranteed minimum price plus a premium for their coffee. A benefit to a guaranteed minimum price is that it establishes a floor of what farmers will be paid and is less volatile than the market price of coffee. Protecting farmers from the whims of pure commodity pricing is one way of creating a more sustainable environment for farmers to operate in.

The chart below, from Nathan Nunn’s 2019 article The Economics of Fair Trade in NBER, demonstrates how the fair trade minimum price can smooth out periods of market price volatility.

A common criticism of fair trade arrangements is that the guaranteed minimum price can inadvertently turn into a maximum price, in that buyers may not voluntarily offer a price beyond the minimum, however that is not the case in more relationship-based transactions.

In direct trade models, prices are negotiated and agreed upon by roasters (buyers) and farmers. Such arrangements are seen as more financially sustainable for the farmers, however they carry their own risks if a buyer decides to back out of a deal.

Transparency is the key to understanding the relationship between the C-price and what is ultimately paid to farmers. Different roasters take different approaches to price, and some are more transparent about that approach than others. At the more transparent end of the spectrum, roasters include a transparency grade as part of their coffee listings, so consumers can see what a roaster paid for green coffee, information which is also a proxy for how much transparency the roaster had into the transaction. Transparency is key for accountability in the coffee trade. The more steps of the supply chain that are fully visible to roasters and consumers, the less room there is for any party to hide something. That, in turn, ensures the coffee is as traceable back to its origin as possible.

Overall, we see that the C-price is considered only as a reference point for a lot of specialty coffee, and as quality differentiation between coffees becomes even more pronounced, further premiums and adjustments to the C-price and fair trade minimum price will be warranted to truly capture the value of the coffee and ensure farmers are being paid a fair, sustainable income. As that unfolds, a new, more efficient method of pricing specialty coffee may emerge.

Once thought to be a straightforward incentive for producers and roasters, coffee certification challenges have become increasingly complex …

Each quarter in our benchmarking report, we analyze a broad sample of single origin coffees from hundreds of small roasters …

You read tasting notes because they promise an experience. Yet the language on coffee bags often feels repetitive …