Your Flavor Road Map: What 1,761 Single Origin Coffees Tell You About Taste

You read tasting notes because they promise an experience. Yet the language on coffee bags often feels repetitive …

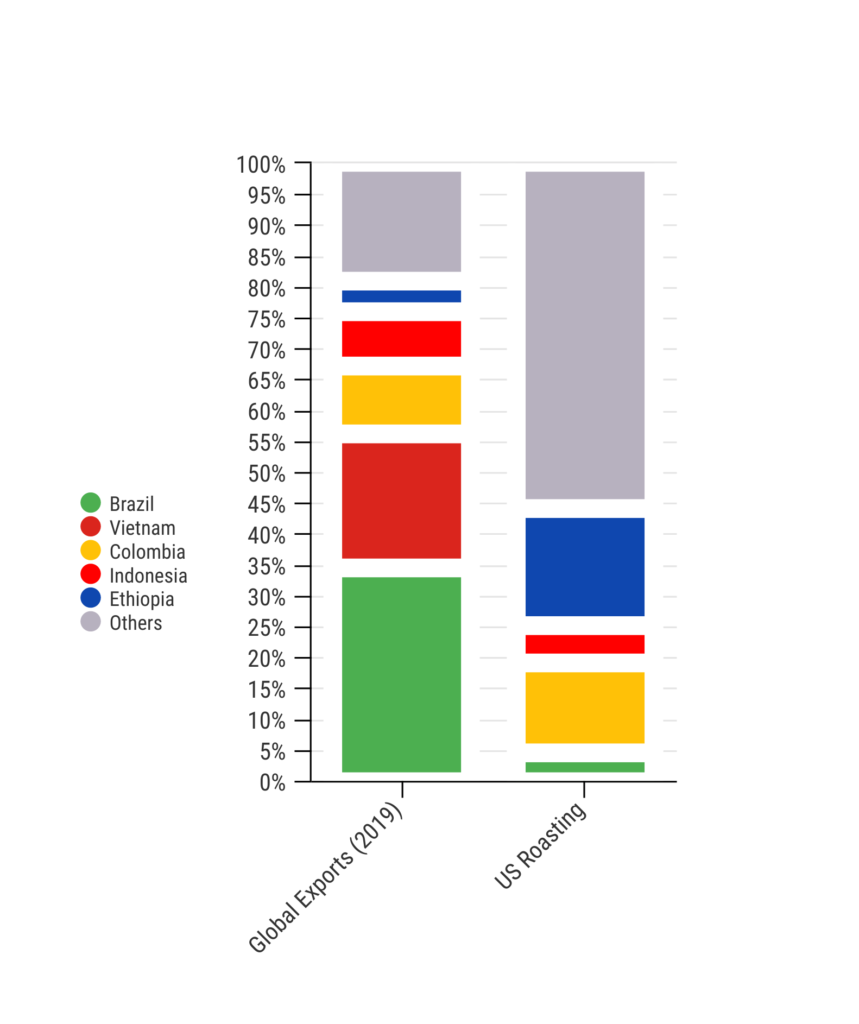

According to the World Atlas, Brazil is the world’s largest coffee exporter, having exported 35% of all coffee produced by the world’s top 10 coffee exporters in 2019. Vietnam was next at 22%, followed by Colombia at 11%. The US, on the importing side, imports the most coffee in the world except for the European Union.

Given this context, you might expect the coffees at your neighborhood coffee shop to align somewhat with global exports (and imports), with a focus on Brazilian and Vietnamese beans and coffees.

And yet, when it comes to specialty coffee in the US, it’s actually quite hard to find roasters who are focused on roasting coffees from Brazil and Vietnam. This is confirmed by our research, in which we have assessed thousands of single origin coffees from roasters across the US.

We found quite a different mix of coffees than what export levels would indicate. In our database of US roasters, just 4.6% and 0.2% of single origin coffees are from Brazil and Vietnam, respectively.

As it turns out, Ethiopian coffee is far and away the most commonly roasted single origin we can identify, comprising 19% of our database, despite representing just 5% of the coffee exported from the top 10 global exporters in 2019.

So what accounts for this disparity between global exports and what’s actually being roasted in the US? Many factors come into play, and we will go over a few here.

First, and perhaps most obvious, is that we need to account for imported coffee going toward blends. And it’s true, Brazilian coffee is often found in blends – but Vietnamese coffee is not. So this still doesn’t fully mirror exports.

Beyond that, flavor plays a substantial role here. A bean’s origin shapes its intrinsic flavor. The flavor profile of Ethiopian coffee is known for floral, fruit, and citrus notes and this bright profile has become very popular in the US for both roasters and consumers, as a standalone single origin coffee. Not that there’s anything wrong with a nutty Brazilian coffee or chocolatey Colombian coffee, but it’s all about relative demand. So while Ethiopian exports account for just a fraction of the global coffee trade, Ethiopian coffees have an outsized influence in the single origin coffee market in the US.

How is it that Ethiopia produces this distinctive profile? Ethiopia’s climate is conducive to ideal coffee growing in many respects, including altitude, natural shade environments, and suitable microclimates, particularly in the southwest part of the country. Altitude, just by itself, has a significant impact on coffee beans, particularly Arabica beans, which happens to be Ethiopia’s sole coffee crop and which are native to the country. All such factors, in various combinations, lead to desirable coffee bean acidity, density and sugar content.

Brazil’s coffee growing regions, although possessing many of the other desirable attributes for growing coffee, are typically lower altitude than Ethiopia, and so do not benefit from the high-altitude cultivation.

Another big reason why Ethiopian coffee is more popular with US-based roasters is that, as a single origin, it tends to be very traceable. Much of Ethiopian coffee is grown by small farmers, with production that can in many cases be traced back to a specific single lot, whose yield can be less than 1,000 lbs per year. Such traceability has become more important for retail coffee consumers in recent years, and this is reflected in what roasters are sourcing and offering.

Brazilian production, in general, is more industrialized and focuses on larger scale operations. This has benefited Brazil’s economy in many ways, as such methods have historically been more about market share and quantity – but quality wasn’t as much of a focus. High-quality coffees do come out of Brazil, but getting that narrative out to the public has been an uphill battle. And the lure of traceability is more powerful when a consumer knows that a coffee can be traced back to an individual farmer rather than, say, a bulk lot facility.

It is important to note that Brazil exports a lot of instant coffee, which is included in global export figures but is, of course, not on the menu of many micro-roasteries. The majority of exports are for ground/roasted coffee, though, so even accounting for the instant coffee, the divergence between exports and what’s being roasted in the US is still substantial.

The reason Vietnamese coffees are not well represented in US roasteries as single origins is likely very simple: coffee production in Vietnam focuses on Robusta beans. Robusta beans grow better at lower altitudes and are one of the two main commercially available bean species in the world (the other being Arabica). However, they have historically not been considered high quality or suitable for the specialty coffee market. That is changing though, as US-based roasters are beginning to experiment with Robusta and introduce it to US coffee consumers, so we just may see more Vietnamese coffees coming out of US roasteries in the years ahead.

In seeing the popularity of Ethiopian beans for US roasters, we can see what US consumers are demanding, relative to other beans. That Ethiopian profile – bright, floral, fruity – seems to be the preferred choice within the US specialty coffee market. Keep an eye though on what roasters are doing with Brazilian and Vietnamese beans, as Brazil steps up its game in the high-quality market and Robusta beans from Vietnam are given another look by more and more US roasteries.

You read tasting notes because they promise an experience. Yet the language on coffee bags often feels repetitive …

You might see organic or fair trade certifications as you look for your next coffee, but bird-friendly brews will be harder to find …

How is new electric roasting technology mitigating coffee’s historical carbon footprint? We talk to Bellwether Coffee to find out …